THANK YOU FOR SUBSCRIBING

If you’ve built fault-tolerant microservices, event-driven pipelines with Kafka, or tuned NoSQL clusters for sub-millisecond latency, construction software will challenge you in new ways. The reality that your systems won’t be deployed in comfortable offices with reliable internet. They’ll run on active job sites where workers wear PPE and deal with spotty 4G signals. IoT devices sync data asynchronously over LoRaWAN or satellite connections. When resource allocation fails, it doesn’t just degrade SLAs. It causes million-dollar cost overruns, regulatory violations, and project cancellations.

I’ve built construction software platforms for over $1 billion in infrastructure projects. This includes 600,000-square-foot data centers and a $950 million terminal renovation at a major international airport.

Construction sites have terrible connectivity. This was the first hard lesson I learned when deploying software to active job sites. I initially built a cloud-dependent system assuming workers would have reliable LTE coverage throughout the day. Unfortunately, this assumption was catastrophically wrong. Workers couldn’t use the app for hours at a time. They would arrive at a site, lose connection, and be unable to access schedules or report progress. The data they entered while offline would fail to sync, creating gaps in our project records.

I rebuilt the entire system with an offline-first architecture. The foundation was a local-first data storage layer using embedded databases on each device. I implemented a state-based synchronization protocol that tracked changes at the operation level rather than the document level. This allowed the system to merge updates from multiple devices without requiring a constant connection to a central server. The conflict resolution layer used vector clocks to establish causal ordering of events. When two users edited the same n schedule element offline, the system could determine which edit happened first and apply a last-write-wins strategy for simple conflicts.

The synchronization engine operated on a pull-based model. When devices reconnected, they would fetch a delta of changes since their last sync rather than downloading entire datasets. This reduced bandwidth requirements and made syncs complete in seconds rather than minutes. The sync protocol included retry logic with exponential backoff to handle intermittent connectivity gracefully.

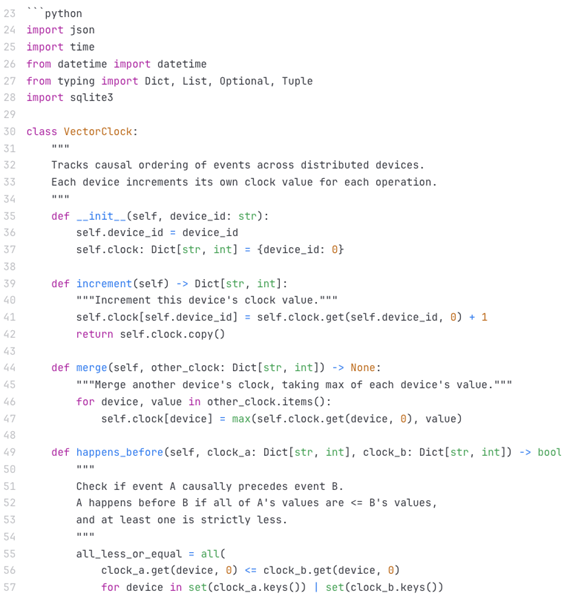

The architecture I’ve described might sound abstract, so I want to show you what this actually looks like in code. This example demonstrates the core patterns in a simplified but functional implementation. It shows how vector clocks track causality, how event sourcing creates an immutable log, and how delta synchronization reduces bandwidth requirements. The example uses Python and SQLite because they’re widely understood, but the patterns apply regardless of your technology stack. The scenario is straightforward. A superintendent and a foreman are both working on the same construction site, updating task statuses on their tablets. Both devices lose connectivity. They each update the same task with different information. When they reconnect, the system needs to sync their changes without losing data or creating corruption. This is the fundamental challenge that offline-first architecture solves, as described below:

The code demonstrates several key concepts working together. The VectorClock class implements the causal ordering mechanism I described earlier. Each device maintains its own clock and increments it with every operation. When devices sync, they merge their clocks to understand the causal relationships between events. The happens_before method determines if one event causally preceded another, while the concurrent method identifies conflicts where two events happened independently on different devices.

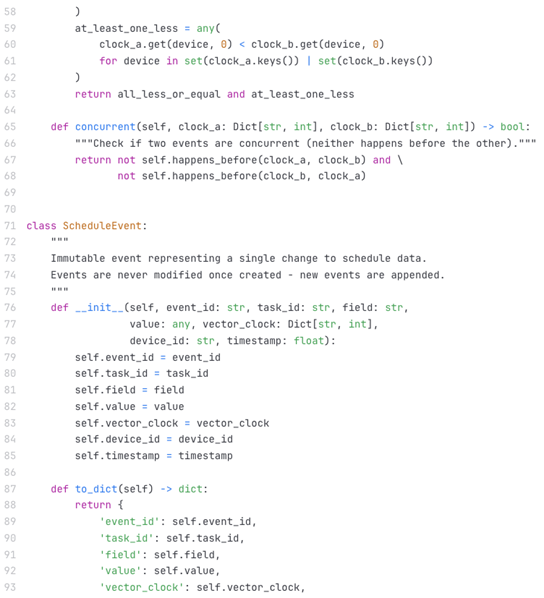

The ScheduleEvent class represents an immutable change record. Once created, events are never modified. This immutability is crucial for the event sourcing pattern. Every state change becomes a permanent record in the event log.

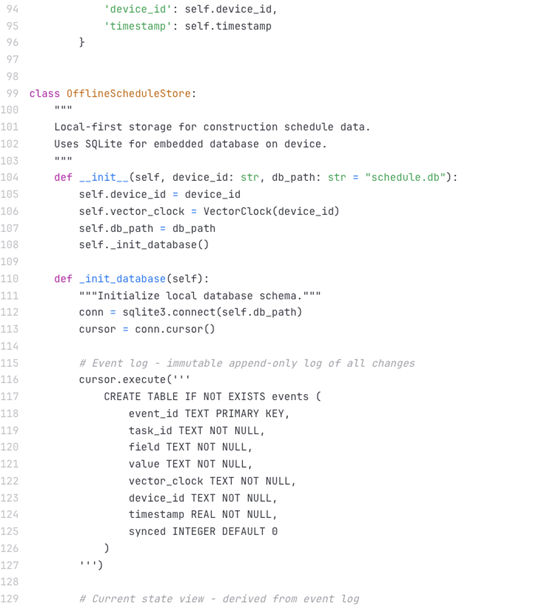

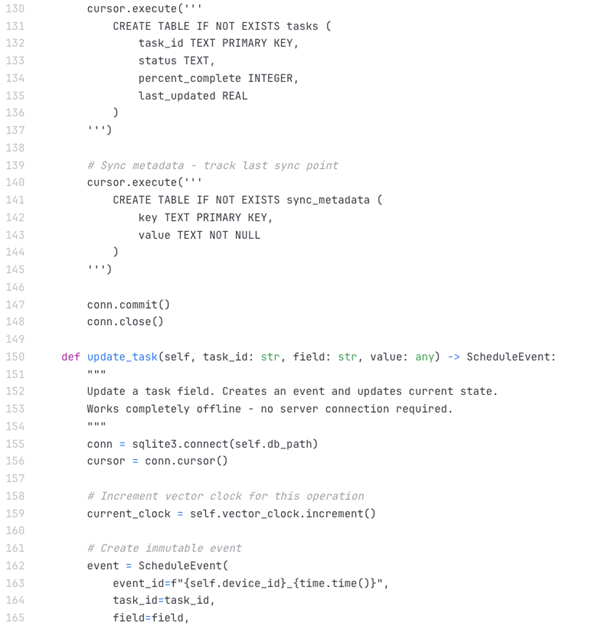

The OfflineScheduleStore class is the heart of the local-first architecture. It uses SQLite as an embedded database that lives entirely on the device. The database has three main tables. The events table is an append-only log of all changes. The tasks table stores the current state derived from the event log. The sync_metadata table tracks synchronization checkpoints. When a user updates a task, the system creates an event, appends it to the log, and updates the current state. All of this happens locally with no server connection required. The synchronization logic in apply_remote_events demonstrates the conflict resolution strategy. When applying events from other devices, the system compares vector clocks to detect conflicts. For simple fields like status or completion percentage, it uses last-write-wins based on timestamps. For complex fields that might have dependencies, it flags the conflict for manual review rather than making potentially incorrect automatic decisions. This balances automatic conflict resolution for common cases with human oversight for complex situations.

The SyncEngine class handles reconnection and retry logic. When connectivity becomes available, it fetches all unsynced local events and pushes them to the server. This is delta synchronization in action. Instead of uploading the entire database, it only sends changes since the last successful sync. The same principle applies when pulling remote changes. The system only fetches events that occurred after the last sync timestamp. This minimizes bandwidth usage and makes syncs complete quickly even over slow connections. The exponential backoff logic in the sync method is critical for handling intermittent connectivity gracefully. When a sync fails, the retry delay doubles up to a maximum of 60 seconds. This prevents the system from hammering the server with constant retry attempts when connectivity is unstable. When a sync finally succeeds, the retry delay resets to one second. This pattern is standard in distributed systems for handling transient failures.

Again, offline-first isn’t a nice-to-have feature. It’s the baseline requirement for any tool that will be used in the field. If your app requires constant connectivity, it will fail on construction sites. Build for offline operation from day one, not as an afterthought. The architectural patterns for offline-first systems are well-established in distributed systems literature, and they apply directly to field software in construction environments. The code example I’ve shown is simplified for clarity, but the core patterns scale to production systems handling millions of events across hundreds of devices.

Copyright © 2025 All Rights Reserved | by:

Copyright © 2025 All Rights Reserved | by: Construction Tech Review

| Subscribe | About us | Sitemap| Editorial Policy| Feedback Policy